Thinking Out Loud

The Sanctifying Joy of Friendship and Conversation

Iron sharpens iron, and one person sharpens another (Proverbs 27:17).

Photo by Matheus Ferrero on Unsplash

I could see it on his face. He had a thought but was afraid to share it with the group. What if he was wrong?

It was his first time attending our Bible study. He was the youngest one there, so, on the one hand, his hesitancy made sense. However, he powered through and shared his thoughts. It wasn’t particularly insightful or refined, but it furthered the conversation and gave the group something to think through together. The next week, our conversation continued. We were thinking out loud and were better for it.

That was the point. We were not a group of guys trying to showcase the pristinely polished goods of our thinking. We met weekly to get our hands dirty, refining each other in the sanctifying act of “thinking out loud.”

The hesitation to share, to think out loud for fear I might be wrong, is not isolated to Bible study groups. The statistics of people filtering ordinary conversations through ChatGPT, for me, reveal a fear of thinking out loud. Perhaps we aren’t sure what to do when a friend says something less than perfect. I’ve heard some raise concerns along the lines of losing creativity and thinking for ourselves, but I want to reflect on something else in the rest of this article. I want to think about being refined through friendship. Specifically, the conversations that sanctify and deepen friendships, calling forth more of us than is possible in solitude.

A good illustration comes from the writing principle that all good writing is good editing.

Editing: Thought Refined

Joel Miller, who worked in publishing for years, wrote a book on the history of books called The Idea Machine. One of the key contributions writing brought to human culture, Millar shows, is the ability to edit. He says, “Writing externalizes ideas, rendering the ideation process itself observable. Subjective thoughts become objects that can be analyzed, challenged, dissected, rearranged, and revised.” Except for emergencies, the first draft is never the final draft. The initial thought, inscribed in a journal, a Google Doc, or on a café napkin, inspires reflection. In one sense, writing fixes our thoughts down and inspires those thoughts to be refined.

“Writing catches ideas in flight,” says Millar, “Inscription fixes them long enough to inspect. Then we’re free to scrap them, settle on them, or even sanctify them. And when we return to them at a later point, we find they are still fixed conveniently where we left them.” (The Idea Machine, 35). Thoughts floating in the abstract space of our mind are easy to lose and near impossible to refine. Writing allows us to return to prior ideas and engage with them again. We can set it down and come back. Writing sets our thoughts for further inspection, where we can chisel away the unhelpful and deepen our thinking. The process of writing, rethinking what we write, and then rewriting what we wrote is a type of sanctification for the life of the mind. Millar says, “Beyond merely representing thinking, in other words, writing is thinking.” (The Idea Machine, 34, Emphasis original).

Let’s take this out of the writer’s room and think about its application for everyone. Our first thoughts usually aren’t clear or well-reasoned. Sometimes they are straight-up bad. How do we get the sanctification of good editing? Conversation.

To use writing as an illustration again, self-editing only does so much. A good editor is like a good friend. Someone who hears your ideas and helps shape and sharpen them. Conversation can do that. We share thoughts, inviting further reflection and refinement through disagreement and questions.

Friendship and The Liturgy of Thinking

There is a rhythm, almost a liturgy to good thinking, between solitude and conversation. Sociologist Sherry Turkle says, “New ideas are more likely to emerge from people thinking on their own.” Outside of the constant noise of endlessly consuming podcasts, new videos, and music, Turkle emphasizes the value of solitude. She says, “Solitude is where we learn to trust our imaginations”(Reclaiming Conversation, 62). Solitude allows for deep reading and creativity, but the insights gained in solitude do not remain there. They are shared and sharpened in conversation.

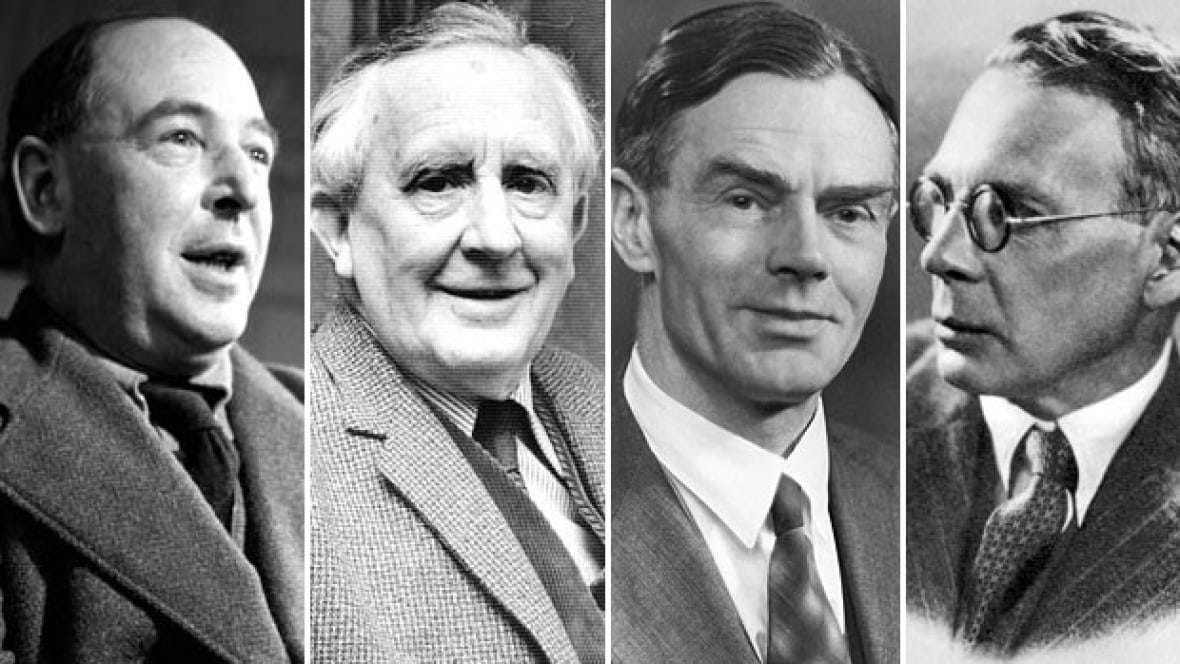

This is one blessing of friendship. As Proverbs 27:9 says, “the sweetness of a friend is better than self-counsel.” The literary friendship of C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and others known as the Inklings exemplifies this sweetness. This group of authors gathered regularly to read their work to one another for feedback, but as Philip and Carol Zaleski note, conversation between friends was the bread and butter of the group.

Conversation was crucial to each session; if the stated purpose of the Inklings was to read and critique one another’s writings, the implicit but universally acknowledged aim was to revel in one another’s talk. Often gatherings had no readings at all, only loud, boisterous back-and-forth on a vast range of topics. Among the Inklings, pen and tongue held equal sway (The Fellowship: the literary lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, 196).

Sometimes the conversation was over a deep disagreement, but this was part of the joy. “Above all,” Philip and Carol Zaleski say, Lewis, Tolkien and the others, “were friend’s, encouraging, provoking, enlightening, and correcting one another” (The Fellowship, 198). Lewis would say of friendship, “In each of my friend’s there is something that only some other friend can fully bring out. By myself I am not large enough to call the whole man into activity; I want other lights than my own to show all his facets.” A solitary person, in some sense, is less than whole. What Scripture says of Adam is true of everyone: “It is not good for the man to be alone” (Gen 2:18). In friendship there is a blessing of thinking out loud that, as Lewis says, calls our whole self into activity.

The Inklings: C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Owen Barfield and Charles Williams.

We lose much when we are afraid to think out loud. Indeed, it takes courage and requires a certain amount of trust. Who would share if they knew they would be torn a new one, or even cancelled?

But thinking out loud, discussion, debate and disagreement all flourish in the safety and refining gift of friendship. Our first thought is never going to be our best thought. But our first thought is the necessary raw material needed to shape mature thinking. Don’t be afraid to think out loud.

Great writing Scott! I think I'll share it with our Bible study group and title if, 'This is why we need each other'.

Thanks for writing!